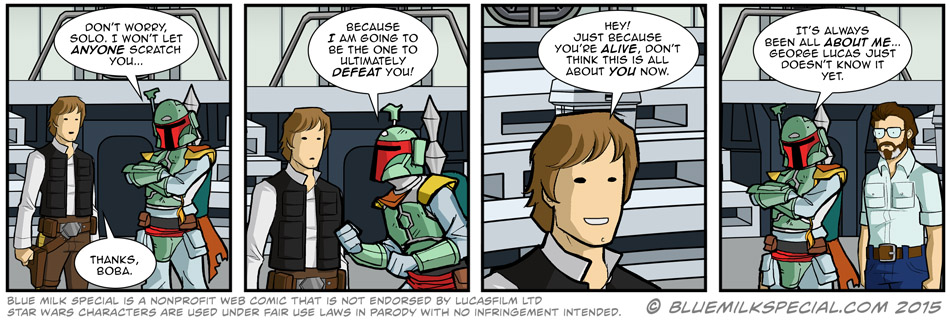

It’s all about Boba, baby!

Hindsight is 20/20. Who knew, at the time, that Boba Fett would practically come to dominate the fandom of the Star Wars universe? In fact, he looks set to win the March Madness poll on StarWars.com yet again. BMS Boba knows he’s important.

For today’s blog, I wanted to share a little piece of the animated sci-world that may be unfamiliar to many of our readers. A while back, I wrote an article about the 1980s animated film Starchaser: Legend of Orrin. I saw the film when I was a kid. The violence shocked me, yet the sense of adventure struck an unusual balance in animated storytelling. I enjoyed seeing something old and new, all rolled into one.

In 1985, Transformers: The Movie led a revolution in animated film that mixed traditional and computer animation. That same year Atlantic Releasing brought their own state-of-the-art animated feature to screens, only they upped the ante by not only employing computer animation but doing so in 3D. Starchaser: The Legend of Orin was certainly an ambitious project and continued in the vein of Ralph Bakshi’s Wizards and Ivan Reitman’s Heavy Metal, pushing the public’s acceptance of mature storytelling in animated form. However, next to Transformers: The Movie, Starchaser is relatively unknown, and it followed closely on the wave of Star Wars mania, generating unfair comparisons that continue to hinder its critical acceptance.

Steven Hahn, producer and director of the project, originally contacted established television animation writer Jeffrey Scott to see if he would be interested in writing an animated feature. “I pitched him an idea that, believe it or not, was based on a fleeting image I had of a past life experience in which people were forced to work in a mine under extremely oppressive conditions,” remembers Scott. “I developed this kernel of an idea into Starchaser (which, by the way, I initially titled Escape to the Stars, which I still prefer).”

Steven Hahn, producer and director of the project, originally contacted established television animation writer Jeffrey Scott to see if he would be interested in writing an animated feature. “I pitched him an idea that, believe it or not, was based on a fleeting image I had of a past life experience in which people were forced to work in a mine under extremely oppressive conditions,” remembers Scott. “I developed this kernel of an idea into Starchaser (which, by the way, I initially titled Escape to the Stars, which I still prefer).”

The film tells the story of Orin, a teenage boy who escapes slavery in the Mine-World of Trinia to the legends of a larger world beyond his people’s subterranean prison are true. Discovering a power within himself, he pledges to return and free his people from their malevolent overlord, Zygon—a self-styled god with schemes of galactic domination. Battling cannibalistic mutant cyborgs, robot security forces, and the criminal underworld, Orin is aided, albeit reluctantly, by the smuggler Dag deBreni and the Princess Aviana.

Today, Jeffrey Scott is probably best known among 1980s animation fans for his extensive work writing on series such as Muppet Babies, Spider-Man, Dungeons & Dragons and Thundarr the Barbarian, however he found writing for film much more enjoyable, being free of the limitations of Broadcast Standards and Practices. In the adaptation of Starchaser from script to screen, Scott said, “the only substantial changes from my script were cut scenes because the script was too long. A lot had to be cut because at that time proportional spaced printers had just come out and I made the mistake of writing in what was essentially a compressed font. So when I reformatted it to Courier it turned out to be a 135-page script, when 90 would have sufficed. Oops!”

Today, Jeffrey Scott is probably best known among 1980s animation fans for his extensive work writing on series such as Muppet Babies, Spider-Man, Dungeons & Dragons and Thundarr the Barbarian, however he found writing for film much more enjoyable, being free of the limitations of Broadcast Standards and Practices. In the adaptation of Starchaser from script to screen, Scott said, “the only substantial changes from my script were cut scenes because the script was too long. A lot had to be cut because at that time proportional spaced printers had just come out and I made the mistake of writing in what was essentially a compressed font. So when I reformatted it to Courier it turned out to be a 135-page script, when 90 would have sufficed. Oops!”

Starchaser is filled with scenes and content that would typically be excised by television censors and certainly is not your standard Saturday morning fair. For example, Orin’s original girlfriend Élan is strangled to death as he watches helplessly in what remains one of the film’s most shocking scenes. But sadly, for many who remember this largely forgotten movie, it remains a fun Star Wars clone at best, and blatant rip-off at its worst.

New York Times film critic Vincent Canby wrote, “Starchaser has two heroes, the youthful, innocent Orin, who looks something like Mark Hamill’s Luke Skywalker, and Dagg, a space smuggler who resembles Burt Reynolds but behaves like Harrison Ford’s Han Solo.” The review continues to compare Princess Aviana to Princess Leia, and a laser beam sword created by the spirit itself to the Force, among others. But then, he also says that “Zygon, the villain who wants to rule the galaxy, could have won a Darth Vader look-alike contest.” Clearly, someone doesn’t remember his villains.

New York Times film critic Vincent Canby wrote, “Starchaser has two heroes, the youthful, innocent Orin, who looks something like Mark Hamill’s Luke Skywalker, and Dagg, a space smuggler who resembles Burt Reynolds but behaves like Harrison Ford’s Han Solo.” The review continues to compare Princess Aviana to Princess Leia, and a laser beam sword created by the spirit itself to the Force, among others. But then, he also says that “Zygon, the villain who wants to rule the galaxy, could have won a Darth Vader look-alike contest.” Clearly, someone doesn’t remember his villains.

The argument that Canby makes, however, is not without good grounds. There are certainly key similarities, but none of these warrant the lawsuit by George Lucas that he vehemently encourages. The truth is that countless space tales from Edgar Rice Borroughs followed by the many great sci-fi pulp authors like John W. Campbell and Poul Anderson (at their height between the 1930s and 1950s) were telling tales of humble heroes and beautiful princesses battling exotic monsters and robots on far-off worlds. Star Wars itself is inspired by the products of this period such as Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers. So nearly all of Canby’s comparisons can be easily dismissed as genre ignorance—all except one…

The three main characters undeniably match Star Wars’ central heroes by archetype. Dag deBremi is irrefutably the Han Solo character, Orin is naïve young hero Luke, and Aviana the Princess Leia. Yet these familiar characters are set apart by nuances in their personality. Dag is much more John Wayne than Han Solo, Orin is much more independent and self-driven than Luke, and Aviana is more honest and naïve than the more practical Princess Leia. There’s even an android woman who is reprogrammed to be madly in love with Dag. I know, you’re thinking that in principle the cast “feels” a lot like it was inspired by Star Wars, and I think it would be impossible to argue that it was now. But as you can see from the description, this is no rip-off.

The plot involves a lot of running around with blaster fire and explosions, but also many of the situations and actions taken by the heroes are quite different. Dag’s raid on one of Zygon’s refining facilities is a great example of an exciting action sequence that has no direct parallel with anything filmed before it. When did Luke Skywalker get captured and tormented by cannibal cyborgs intent on dissecting him? These variations on the theme deliver an exciting pulp adventure that manages in places to be far darker than Star Wars. In fact, while similarities with the central heroes of Star Wars do exist, this feeling of familiarity never pervades to such a degree that it detracts from this being a memorable space epic in its own right.

“One of the underlying themes in the film is that man is a spiritual being,” explains Scott. “I tried to express [this] by the ‘starflies’ that ultimately turned into the wise men and women at the end. This was also demonstrated when Orin, given the opportunity to move on, rose above his body for a moment, before deciding to continue his corporal existence. A deeper expression of one’s spiritual potential was expressed in Orin’s ability to create his sword by his intention alone. Zygon’s bewilderment at this was my way of showing the duality of spiritual and materialist viewpoints, thus Zygon couldn’t fathom how such a thing was possible.”

What we have in Starchaser is a fine cinematic example of the fantasy sci-fi epic. To argue that Starchaser rips off of Star Wars is to say Mission Impossible rips off James Bond—while the latter are examples of the action-spy genre but are certainly not examples of plagiarism. Perhaps Vincent Camby was only blowing hot air, but even as a child, when I saw this film, I felt it was stealing from Star Wars. Yet, now when I watch the film as an adult, I see all the brilliant things that Star Wars never did, and beyond the odd shared archetype and theme, Starchaser is an excellent alternative cinematic example of the space opera genre.

Perhaps Starchaser would be better remembered today had it been marketed more as an roaring adventure than a spectacle film. During a lunch together, Scott mentioned to Hahn that he would love to make an animated film in stereoscope 3-D. According to Scott, this conversation inspired Hahn to make Starchaser Atlantic Releasing’s first stereoscopic film, ultimately boasting the promotional tagline “The Best 3-D movie ever made!” In hindsight, Scott notes that this turned out to be a mistake, causing the film to go way over budget and contributing to the studios losses after its release.

Although it would be easy to join the short-sighted bandwagon that likes to focus on the superficial and mislabel the film as a Star Wars clone, this overlooks the fact that Starchaser: The Legend of Orin offers an alternative to Star Wars rather than a reinterpretation. With characters like anti-hero Dag deBreni and philosophizing technocrat Zygon, perhaps the film’s true 3-Dimensional quality is its characters.

I enjoyed it.

Added to my list. 🙂

… for a brief moment, when I saw the horses, I instantly thought of Galtar.

I’ve never seen Galtar.

Hey I caught up, awesome! I love BMS, and now that I’m a Star Wars rather than just a Nerd, I appreciate it more (knowing what actually happens in the Holiday special helps a lot).

And I have a question: Will Anakin’s Force Ghost keep the Mug? (Please say yes)

Wow, I saw this once, something like 25 years ago and could only remember fragments of it. Glad to be able to finally put a name to it.

Starchaser: Legend of Orrin! god that’s going back a bit 1985 apparently, don’t remember the 3d (or at least i don’t remember having to wear 3D glasses